Why Don't We See It Coming?

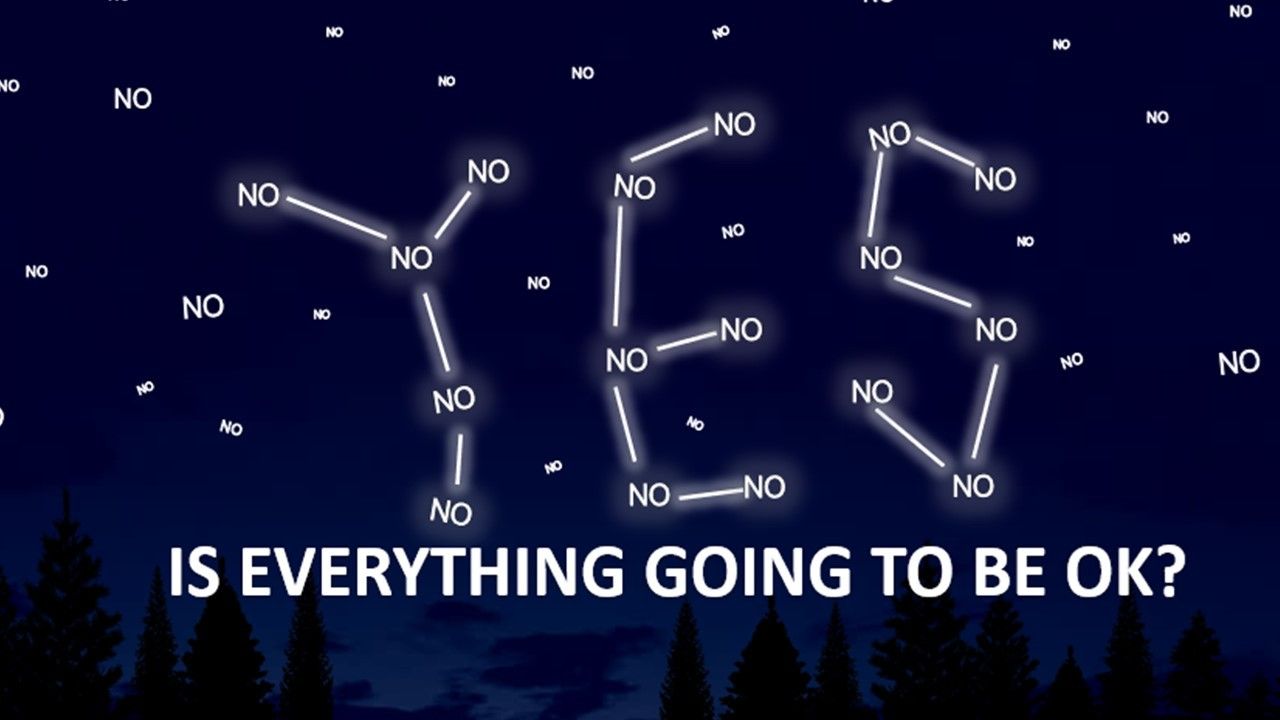

"Is Everything Going to Be Ok?"

The Danish philosopher, Søren Kierkegaard, wrote that "Life is lived forwards, but understood backwards". By which he meant, I guess, that sometimes we have to make our own mistakes before we can hope to understand why we made them. If that's true, then it's cold comfort to investors now scrambling to try and get something back from Indian electric vehicle maker BlueSmart Mobility, but it's worth remembering that we've definitely been here before.

It was back in 2008 that financial journalist Alex Dalmady stuck his neck out and did what so few had done before. Risking potential bankruptcy and ruin (or worse...) he publicly called Stanford International Bank (SIB) as a fraud before the ponzi scheme there had been discovered. And he did so using his 'Duck Theory' - as in 'If it looks like a duck, and it quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck!' The Duck Theory had four main indicators which applied to SIB, and it's instructive to see now how they slot not only into more recent cases such as FTX but also into many of the other fraud “classics” of the last few decades:

👉 "It's too good to be true." - FTX, so youthful, was sponsoring major sporting events and venues costing hundreds of millions. Just as SIB and Sir Allen Stanford did with international cricket.

👉 "It can do what no-one else can do." - FTX was offering returns at significantly above-competitor rates. Just like Bernie Madoff and his ‘elite-only’ funds.

👉 "There are only a few people, or one person, overseeing everything." - FTX management - and financial management (in a complex business) - was tightly controlled with limited genuine external oversight. Just like Nick Leeson and Barings (remember them, Old-Timers?) all those years ago.

👉 "There are very few incentives for whistleblowers." - Well, are there ever? But with massive investment rounds, huge celebrity endorsements, stunning growth multiples and a Rockstar CEO, based and regulated in an easily-impressed offshore jurisdiction and pumping cash (real, fiat cash) into good causes, who wanted to analyse the actual chemical contents of such a punch bowl? Sub-prime mortgage/CDO scandal, anybody?

Of course, (and as Kierkegaard may have known), the problem with these types of 'red flags' is that whilst they are commonly found in frauds which have occurred, in themselves they cannot accurately predict fraud because they are too widespread, i.e. they can be found in businesses and situations where fraud and cheating have never been discovered because they have never existed. As an example, I have waited for years for 'explosive revelations' about how the New Zealand All Blacks manage to score so many points in the final quarter of a game. But no, just a lot fitter and more determined it would seem than most teams that they play. At most, these red flags can help us by telling us where to look more closely. And it is there that we encounter the real problem in all this - that the most common fate of those who shine a light and report a problem is...

To be ignored.

Consider; there were warnings - in some cases multiple warnings over several years - of trouble afoot in Wirecard, Danske Bank, The sub-prime mortgage market, the Madoff Funds, Enron, WorldCom and many more. These warnings came from informed, educated, not-obviously-insane people, in many cases insiders with a deep knowledge of the industries and sectors concerned. Yet no meaningful action was taken. Why?

The full chains of causation for each are unique, but in seeking to 'understand backwards' so that we can at least try to 'live forwards' in a more savvy and alert way, it's worth remembering some truths about human nature that I would go so far as to say are profound - i.e., inescapable.

- We are overly optimistic - 'Optimism bias' in humans is well established in the literature of psychology (e.g. see Optimism Bias). Maybe it's nature's saving mechanism for our species which, uniquely, (so far as we can tell) is self-aware of its own mortality, but we sure do like to look on the bright side. It may happen to others, but it won't happen to us. At senior levels within organizations this can translate into an unwillingness to believe that the worst is possible. "Nothing to see here. Everything's going to be OK, trust me!"

- We don't like to receive bad news - or deliver it - 'Shoot the messenger' is an instinct as old as bad news itself. In a 2019 study series, a team from Harvard found that participants generally saw the person who delivered negative information as less likeable. And the more unexpected the bad news was, the more upset the participants were. It's not hard to see the application of this in corporate settings. "I really wish you hadn't told me that. Why do you always have to do this?"

- We seek out data which confirms what we already believe - And we ignore or explain-away data which contradicts it. Confirmation Bias is another apparently universal trait established in multiple experiments. In a world teeming with information, it's essential that we have mechanisms for shutting out 'non-essential' data. But where corporate malfeasance is a possibility, a capacity to pay special attention to information which doesn't fit with existing 'hunky-dory' assumptions is not only advantageous, it's essential.

- We don't like being the 'odd-one-out' - The trait of 'conformity' is another one that's been well established ever since Solomon Asch conducted his 'stick-length' experiments which showed people's preparedness to answer simple questions incorrectly in order to 'fit in' with the group - despite the evidence of their own senses. "Why take the risk of appearing panicky and credulous in the face of dire warnings, when no-one else appears to be doing so?" And "How am I going to explain why we chose not to make an 80% investment return, when so many others did?"

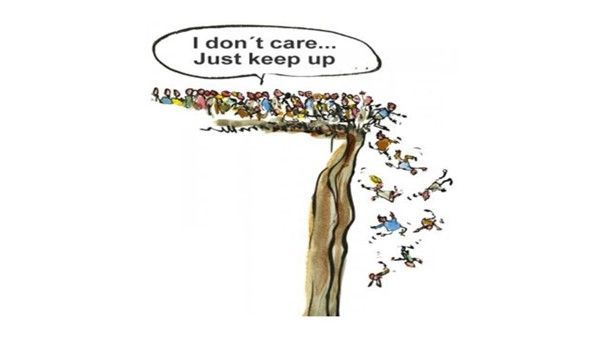

- We tend to do as we are told - The 'electric shock' experiments run by Stanley Milgram at Yale in the 1960s are well known enough by now to have entered public consciousness. Milgram found that a startlingly large proportion of people would administer what they thought were lethal electric shocks (they weren't) to complete strangers when instructed to do so by an authority figure. Again, possibly (but not exclusively) at lower power/influence levels within organisations, a simple instruction from a superior to ignore a report or a warning may be all that's required.

The next time anyone has to write a report, professionally, within or about an organization concerning a suspicion of some kind of hidden problem with potentially severe consequences, I would suggest that some kind of summary of the above traits be included in a preface page, as a warning to those who are about to read it. Because, to end with another quote, this time from Nobel prize-winning physicist, Richard Feynman:

"The first rule is not to fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool."

Richard Feynman

Tim Parkman

Managing Director, Lessons Learned Ltd

16th June 2025

If you like consuming your Compliance content in the form of Bro/Sis-banter podcasts, then here is an AI generated podcast of this article. Prep time – 3 minutes!